“The World Still Sings” is a documentary film of the 1964 International Eisteddfod, directed by Jack Howells and produced jointly by Howells’ own company and the Esso Petroleum Company, Ltd. In 1962, Howells won an Academy Award for his documentary of Dylan Thomas, and at the time of the Eisteddfod film he was working for ITV on a film about Aneurin Bevan. By opting to film the Llangollen Eisteddfod he placed the festival firmly in the pantheon of Welsh icons.

The title responds to lines from Dylan Thomas’s 1953 radio broadcast about the Llangollen festival:

“Are you surprised that people still can dance and sing in a world on its head? The only surprising thing about miracles, however small, is that they sometimes happen.”

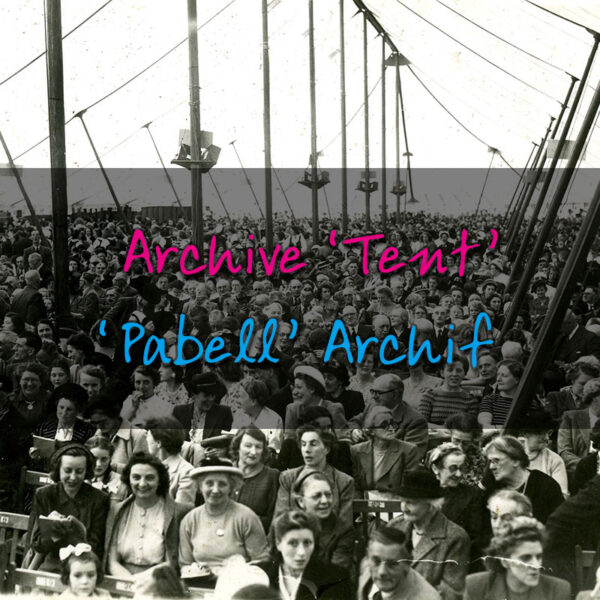

The film of the 18th Llangollen International Musical Eisteddfod in 1964 captures the festival at the height of the highly successful early period. Its focus is on the competitors, as was all the newspaper and broadcast coverage. There were competitors from 17 countries in addition to the United Kingdom, and about 20 choral or dance groups in each of the major competitions. The winners came from West Germany, England, Italy, Ukraine (ex-pats from Manchester), Portugal and Sweden.

You get a glimpse in the film of the prestige then attached to the event. There was a royal visit (Princess Margaret and the Earl of Snowdon). The new Secretary of State for Wales attended. TV coverage was UK-wide, and led by senior presenters who spent the week in Llangollen. Reporters and photographers came from all major newspapers and news agencies. The field is packed every day. Also evident from the film is the way that the festival spreads through the town, hardly surprising when many of the competitors stayed locally. Spontaneous late-night singing and dancing filled the homes and hostelries.

Unlike today, the concerts got little publicity. They were filled with the competitors doing special pieces. The professional performers included: a Spanish Harpist; and Geraint Evans, popular Welsh baritone. The opening concert presented the Czechoslovak National Ballet; the week closed with massed brass bands.

Look carefully at the film and you will be struck both by the contribution made everywhere by volunteers, and by the lack of commercialisation. Apart from a few food stalls, there are no concessions on the field. The small tents have a strong utilitarian ethos, typical of the festival: post office, Wales Tourist Board, newspapers, banks, organisations promoting international cooperation. Despite its policy of keeping ticket prices as low as possible to encourage attendance, the Eisteddfod more or less broke even; grants from the Arts Council for Wales and very recently from local authorities were used for improvements, not to defray running costs.

Look even more carefully and you’ll spot current Chairman Rhys Davies as an angelic young lad.

Lastly, the origins of the film are a bit of a mystery. The initiative came from Esso, who approached Jack Howells, but there are no papers about the film in the Jack Howells archive in the National Library of Wales, and Exxon Mobil couldn’t supply any insights. It is perhaps relevant that at the time all the large oil companies were promoting tourism as a way of increasing petrol sales. Nevertheless, the choice of Jack Howells as director was inspired. His documentary of Dylan Thomas had won an Oscar in 1962, and he had a way with Welsh subjects. He captured the Llangollen International Musical Eisteddfod in a good year.

Enjoy!

Chris

Chris Adams

Archives Committee